Original Copyright 1984, last update 1-10-23 / 7,618 words by Jon Kramer

Nonfiction. These events took place forty years ago in 1983.

PROLOGUE – This is a long story – appropriately so, considering the length its shadow has cast over the lives of me and George. I wrote the initial part about a month after getting out of LDS hospital, on a grocery bag (for lack of a pad of paper; this being well before there were such things as plastic grocery bags) during my time at Mayo Clinic which, from the perspective of an emaciated, wracked, adrift survivor, was anything but cheerful. Certain parts may seem unbelievable and/or implausible. But the details are factual, and the events played out as described to the best of my memory both then and now. It’s not as fun a story as I usually like to produce. But it is useful if you wish to understand a little about Kracken’s inner workings and the reason he is the way he is, for better or worse.

You’ve heard that old saying: What you don’t know won’t hurt you. God only knows what ignoramus came up with that one, but take it from me, it’s top-shelf bullshit. What you don’t know can indeed hurt you – even kill you in strange and bazaar ways. This story demonstrates it.

In the summer of 1983, George and I drove west in Betsy – my ramshackle, blue, Dodge window van – to attend Geology Field Camp in the mountains of central Colorado. For six weeks we lived, worked, and smoked a little pot at 8,200 feet above sea level while completing credits for our geology degrees at the University of Maryland. After Field Camp, we continued west on a fossil hunting adventure to southern California where we met up with a schoolteacher friend, George Ast. He took us to some oil-oozing tar pits a few hours north of Los Angeles in search of Ice Age animals. By the time we got there in the late morning, it was Hell-on-Earth hot. This was late July, I should add.

Initially, we were going to stay only for the day – collect some fossil insects and move on. But to our surprise we stumbled upon a bed of Pleistocene animal bones which included ancient birds and mammals, the skull of a rare Ice Age bear, and legs of a Saber-toothed tiger. There was a veritable potpourri of Pleistocene skeletons, large and small, entombed in the tar-seep sediments.

Having the advantage of being gainfully unemployed, George and I decided to stay and dig out the bonebed while Mr. Ast went back to the air conditioned comfort of his classroom. Little did we know that we’d just made our life’s most fateful decision.

The dig site was in the midst of a scorched desert moonscape of tar sands, sage brush, and oil derricks near Maricopa, California. Bubbling “pots” of pure, hot tar dotted the landscape, oozing out from cracks in the Miocene strata and flowing atop the desert sands much as they have been doing for many thousands of years, trapping insects, plants, and animals alike. It’s still going on today.

The land was owned by Texaco. In an effort to retrieve more oil from the reluctant beds below, they were experimenting with pumping steam down the wells to loosen up the crude. (This was long before fracking.) As it happened, not far from our fossil site was a steam plant. Early on, we made friends with the roughnecks and “pump boss” there. They gave us permission to dig and camp in the desert next to our excavation. For a week we lived as desert rats in Betsy, gleefully excavating bones.

The land was owned by Texaco. In an effort to retrieve more oil from the reluctant beds below, they were experimenting with pumping steam down the wells to loosen up the crude. (This was long before fracking.) As it happened, not far from our fossil site was a steam plant. Early on, we made friends with the roughnecks and “pump boss” there. They gave us permission to dig and camp in the desert next to our excavation. For a week we lived as desert rats in Betsy, gleefully excavating bones.

Before the trip I installed a cassette tape deck in Betsy, along with an amplifier that ran two sizeable cabinet speakers. I called the contraption “Wimpy” after the Popeye character who was constantly hungry. Today Wimpy would have instant street cred as it could easily compete with the subwoofer-clad doofuses that drive around blasting their sonic cannons until their heads explode.

But back then I didn’t care the least about being cool. The simple fact was I had no budget to spend on a sound system for Betsy. So, I just took what I had in my room at home and installed it in the van. Being practical, we used the two cabinet speakers as legs for our onboard desk.

While we dug bones and threw dirt around, we listening to Jimi Hendrix, Frank Zappa, CCR, and The Band. As everyone who owned one knows, cassette players were notorious for malfunction. Just as the cartoon character of Wimpy ate hamburgers for a living, our Wimpy sound system ate cassette tapes. On a regular basis. As a result, we became necessarily proficient at extracting the mangled strands of cellophane and splicing them back together. It got to the point where many of the tunes were laughably shortened. One of my favorite Jimi Hendrix’s tunes, for example, was thoroughly eviscerated. The Wind Cries Mary does not go like this:

After all the jacks are in their boxes,

And the clowns have all gone to bed,

You can hear happiness staggering ….

……screech, screech, crack, screech…

… it whispers, “No, this will be the last”.

And the wind cries “Mary”.

Despite the tragedy of the lost verses, at least it still had the final precious cords following the lyrics. To this day I never tire of hearing those masterful notes. Whenever I have the chance, I replay them over and over.

The late July days were sizzling – passing 110 degrees on a regular basis. By 11:00 we were forced to shut down the excavation and head to town for a cool swim in the municipal pool. In the evening, we returned and continued digging for a few hours. Late at night we’d head over to the nearby steam plant to cool off in their AC and shoot the breeze with the workers. It was a grueling, grubby, miserable existence. But despite the heat, the hardship, and the grime, we were loving it! To us this was real living: Viva la vida!

Remember I said what you don’t know can hurt you? Well, here it comes: As we excavated, what we didn’t know was that the dust layers we were digging through were heavily laden with the spores of a toxic fungus – Coccidioides. It lives in the sagebrush that’s ubiquitous in this desert. Year-over-year these assassins shed billions of microscopic spores that accumulate in the dirt and float freely in the air. They’ve been piling up in the dust for 100,000 years. That’s a lot of dust, and an immeasurable amount of “Cocci” spores.

We didn’t know. You cannot see them, you cannot hear them, you cannot feel or taste them. But the spores of Coccidioides are there – by the gazillions! – ready and waiting to wreak havoc on you. It’s like a science fiction horror film. Invasion of the Body Snatchers comes to mind. You blithely invite them in, and they kill you.

Despite the wickedly hot temperatures, George and I followed the bonebed down into the earth, carefully excavating a trove of fossils the likes of which we’d never found before. We eagerly scratched out a hole about six feet deep and tunneled underground along the layer. Dust clouds swirled around us in a constant storm of airborne debris. We were hurling sediment out of the pit like dogs after a bone. The air was a fog of dust and spores, a lot of which ended up in our lungs.

After a few days, a local Boy Scout leader visited our excavation. Seeing our dust-clouded excavation in process, he was aghast. He warned us about Valley Fever – a local disease known to hit archeologists and paleontologist working in the area. He impressed on us the potential seriousness of our situation and recommended we talk to the staff at the local clinic. The next day, when we went to town, we stopped in at the local hospital.

The docs at the clinic were all-to-familiar with the disease. Scientifically it’s called Coccidioidomycosis, aka “Cocci”. They gave us a photocopied page from a large, red medical manual called the Physicians Desk Reference, or PDR (this was before computers, when actual books were used as references). It gave a rundown of symptoms associated with Cocci. The disease is a fungus that attacks the lungs and can sometimes become very severe. In really serious cases it can be fatal. It’s known for disseminating and attacking the vital organs, gradually killing the host.

The staff encouraged us to wear dust masks. We bought them, wore them, and continued digging like hell. But, in hindsight, by the time we donned the masks, we had already inhaled way too much spore-laden dust. The clock had begun ticking…

On average, Cocci takes seven to ten days to manifest symptoms. After you breath them in, the spores activate inside your lungs and grow into fungus. As it happened, on day seven the bonebed petered out and we finished the excavation. We packed the van, said goodbye to our steam plant friends, and hit the road early the next morning. We felt great, traveling with many dozen fantastic fossil specimens in the back of Betsy.

Heading north on I-15, we reset our minds for the next phase of our adventure: the Tetons! We had arranged to rent horses for a pack trip to a fossil site high up in the mountains at Emerald Lake. Our route north took us through Salt Lake City where, on a whim, we stopped to visit George’s uncle – Howard Sloan – who graciously provided us our first civilized luxuries in over two months. A hot shower and clean bed never felt so good!

The following day we awoke feeling a little groggy but attributed it to the arduous desert digging, long drive, and the few beers we’d consumed the night before. Howard implored us to stay a couple more days. We figured another night of good rest and home-cooked food wouldn’t be a bad idea.

The next day was the beginning of the end.

By noon the following day we each began to feel a growing pain in our lungs and knew it was Cocci. As a precaution, we asked Howard to take us over to Cottonwood Community Hospital, not far from the house, just to get checked. We walked in and announced to the doctors that we had Coccidioidomycosis. They, being doctors, were of course skeptical of two long-hair Hippies marching in and self-diagnosing their ailment. So, they ran a bunch of tests and kept us sitting in the ER for several hours while they puzzled about our symptoms. They’d never seen anything like it. Finally, they came back and announced – Looks like you have Valley Fever! Valley Fever = Coccidioidomycosis.

Telling us what we already knew, they went down the list of symptoms associated with various degrees of Cocci severity, reading from a familiar-looking photocopied page. When we got a glimpse, we saw it was straight out of the same PDR we’d seen in California. At least the medical profession was consistent! But, as a result, the clinicians were unconcerned.

Research shows, they announced, over 90% of these cases have only mild symptoms. You guys are in the peak of health, so you’ll be fine in a few days…. Go home, take it easy, and don’t worry about it.

Four hours sitting in the ER – with who knows how much in hospital costs piling up – and all we got for it was a second photocopied page identical to the one we had already received – free of charge, mind you! – in Taft. Now George and I each had our own copy of the PDR Cocci page…

Nonetheless, affirmed of our immortality, we returned to the house. We decided – come hell or high water! – we would continue on to Wyoming the next morning. Each day we waited to leave would cut into our time in the Tetons. Besides, we were just given a hall pass by the medical team at Cottonwood. So, even if we didn’t feel 100%, we figured on toughing it out while driving down the road. rather than waste more time laying around Salt Lake City. After all – we were young, and fit, and there were fossils waiting for us in the mountains of Wyoming! No doubt we’d feel better just getting back into the field and digging.

We awoke the next day feeling worse – much worse. The pain in our lungs was acute and severe. By now we were coughing – a lot. However, despite our advancing illness we abided the stubbornness of youth and packed the van to leave. Howard and his daughter were clearly concerned. Stay a couple more days and get well, they implored. But even in our sorry state, we didn’t want to impose on them any longer. The two Hippies were eager to get going and the Teton mountains were calling!

After some curb-side hugs, we climbed aboard and started Betsy – or rather, didn’t start Betsy. Initially she turned over and seemed about to start – as always – but then came a tremendous “bang!” The motor spun wildly, but she would not fire up. Although we had no idea at the time, it turned out she’d blown the timing chain. The old gal had over 100,000 hard miles on her, so it was about time. But that threw the proverbial monkey wrench into our leaving.

And… it saved our lives.

We looked under the hood trying to find the source of the problem. But timing chains are hidden and not easily diagnosed. As time ticked by, our symptoms got worse. Both of us began getting short of breath, started panting, and feeling light-headed. We soon found ourselves too sick to carry on the investigation and elected to stay another day or so until we felt better and could fix the van. We really had no choice. Betsy wasn’t going anywhere, no matter how determined we were to go ourselves.

That night things really went haywire. We were each coughing and hacking so much we couldn’t sleep. By morning we were experiencing major shortness of breath – panting like dogs -while the pain in our lungs became more and more intense. It was like they were on fire. By afternoon we were getting dizzy and nauseous. Disturbingly, a strange red rash started to form on our skins and started to advance over our bodies. Our vision blurred and we had trouble keeping our balance.

When you cannot breathe there is a full-on panic attack in your body. All the vital organs start screaming at once: Send us oxygen! Your system goes into shock. Our situation was getting more desperate by the minute – we were doubling-over in coughing fits. Howard insisted we go back to the hospital. He helped us to the car and drove us back to Cottonwood.

We saw the same docs as before. They were visibly alarmed. Our blood oxygen saturations were going down like a sinking ship. They thought about admitting us right then but ultimately decided if things got worse, they’d be ill equipped to deal with it. Instead, they sent us to LDS hospital in downtown Salt Lake City, calling ahead to alert them of our arrival.

By this time, we were getting so light-headed we could hardly walk so we got into wheel chairs. In and out of delirium, they wheeled us into the LDS emergency room on a Friday afternoon. The ER doctor was obviously unfamiliar with our condition but was of the opinion we were simply experiencing panic attacks brought on by our shortness of breath. He had no idea. Finally, after a 40 minute absence, he came back and told us the exact same thing as the docs at Cottonwood: What you have is Valley Fever. Now, 90% of these cases resolve after a few days…

George and I looked at each other. We could hardly believe our ears – this guy was reciting the same PDR rhetoric we had heard thrice in the last week! We were hyperventilating like rabid animals and here he was reading to us from a worn-out script! Mustering as much vocal strength as I could, I declared hoarsely, We’re NOT leaving! We can’t breathe! WE… ARE…. DYING…

The ER doc was young and a bit put off by this. He called the staff pulmonary physician, who had already left for the day. Dr. Benowitz came back to the hospital and saw us 45 minutes later. The situation had continued to decline. But he had no experience with Cocci either, so he consulted – guess what! – the PDR! – and came to the same conclusion as the ER doc.

Benowitz, like the other doc, was in uncharted waters. At first, he was of the same mind and tried to assure us our illness would reverse and resolve itself in short order. We, on the other hand, knew we were dying and flat-out refused to go home. Sort of jokingly, George told the docs it would be wholly inconsiderate of us to die at his uncle’s house.

We’ll just stay and die in the waiting room here… he wheezed.

Eventually, Benowitz and the other doc agreed on a more sensible plan: We think you’ll be fine very shortly. But there is a slight chance it could get worse. So here’s what we’ll do: We’ll admit you both for the weekend to keep an eye on the situation. If you are better by Monday morning, then you go home, okay? There was no argument from us on that idea.

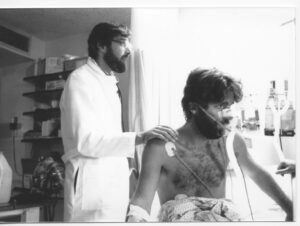

We were finally admitted to LDS Hospital about 5pm. Much to everyone’s surprise – but ours! – things slid downhill in a hurry. Our breathing became so rapid we could not count the rate even if we were capable of maintaining consciousness, which we were not. (Our panting ultimately exceeded 70 breaths a minute). The nausea got worse, and we were blacking out. When awake, we slurred our speech while floating in and out of lucidity. Because of our hypoxic condition, the bright red rash was now covering a large portion of our skin. We were sweating profusely, soaking the bedsheets every hour. Our bodies started to have uncontrolled spasms. We’d arrived in hell.

By 11pm – barely six hours after being admitted – we were moved to Intensive Care. An hour later we were moved again – into a specialized Respiratory Intensive Care unit – and put on ventilators. George was in such bad shape he had to be intubated. I was put on a pressure mask. There were only 3 beds in the specialized ICU and we occupied two of them for the next week.

After you breathe in the spores of Cocci, they germinate and start to grow the Coccidioides fungus in your lungs. The way your body copes with such an invasion is to smother it by drowning it in fluid. But, in severe cases, that compounds the problem. The more spores you inhale, the more the fungus grows, and the more aggressively your body reacts to smother it.

We had imported a huge inoculum of spores in the four days we’d been digging without masks. In a very severe case like ours, the lungs fill with fluid and you eventually asphyxiate yourself, dying from lack of oxygen. You effectively – very effectively! – drown yourself. In the Southwest there are over 200 deaths reported each year of people who have been suffocated by Cocci. The actual number is probably much higher.

Our situation was critical and getting more so by the minute. Within a short time, the oxygen in our ventilators was cranked up to 100% and being forced in under pressure. Even so, oxygen levels could not be maintained. But the ventilators did buy us some time. The doctors – Larson, Benowitz, and Morris – conferred with colleagues in LA which had the most experience with the disease. The head physician happened to be Albert Einstein’s nephew. They all realized our cases were off the charts – there was no protocol for it. The staff was navigating by dead-reckoning.

Together the physicians decided to take a long-shot gamble. Since the most immediate problem was flooding of the lungs, the first thing to do was to curtail the fluid buildup. They tapped our lungs and drew off liters of fluid. At the same time, they administered a powerful diuretic – Lasix – in huge amounts. It was an attempt to dehydrate us and stop the flood. From the start, they maxed out the dosage. It was a desperate play. Even so, our lungs continued to fill and the oxygen saturation levels kept dropping. The end was nearing, and all too fast.

Along with these developments George and I slipped off the face of the planet. We were completely unconscious. I cannot speak for George and how he remembers this time, but I had a strange disconnected awareness. They call it an “out-of-body death experience”. I found myself deep inside the chaos of my world, fighting my life’s biggest battle. Even in the truly hopeless state my body and mind were in, I knew this was all-or-nothing war. I was desperately trying to hold on. Eventually, though, the darkness poured over me and I slipped away.

I felt myself being drawn through a tunnel as if caught by a fast-moving river. The tunnel was formed by images of my past – all my past. It was surreal. My entire history replayed before me as I was carried along: I was 5, playing with my two brothers and sister on the hard coral beach of Staniel Key, just beside our family boat. I was 8, jumping with my brothers and sister into a dirty snowbank at the seedy tenements where we lived in Riverdale, Maryland. I was 16, arguing with my parents in our cramped apartment in Rockville. I was 19 on a double-date with my brother Bill – we were dating two sisters and stuck in DC traffic during the US Bicentennial celebration. It was all there. The history reels played quickly and completely, flowing continuously right up to this present moment in the ICU.

Then, suddenly, I was out of the tunnel and fell free of all Earthly things. All physical aspects evaporated. All feelings and emotions dissipated. I didn’t think at all – I didn’t need to – I just sensed everything. As I left the tunnel, I became adrift in a quietude, floating in a warm, encompassing glow. It felt totally natural – like this was the way things had always been… forever. There was nothing to it at all – just quiet, comfortable, serenity and a heightened awareness of everything happening around me. It was like being in a dream.

I found myself sensing the area of my surroundings in the ICU. I was floating above it all, looking down on a theater scene. I could see and hear everything at the same time. I was gone from the world and was now an observer of it, like Dickens’ Ghost of Christmas Present. I didn’t influence the scenes, just watched them unfold.

I witnessed a serious meeting of the doctors in the ICU and felt nothing about it at all. I saw the concern in the faces of the nurses as they tended our struggling bodies. I studied George and myself, our bodies entangled in tubes, wires, and sensors – surrounded by bleeping machines and pulsing screens. I was looking at me and my best friend on our death beds. But I didn’t care – I had no feeling whatsoever one way or another. I wasn’t happy, I wasn’t sad. I wasn’t anything at all. Just an observer with no feelings.

In the strange chronology of our situation, it had become apparent that whatever happened to George, would befall me within an hour. He was first to be moved to the ICU, first to be ventilated. As I floated above this world of artificial life support, with all its beeping, buzzing and chirping machines, it occurred to me the curtain was coming down on our lives. The Grim Reaper was waiting here in the shadows – waiting anxiously. He had come for George and I.

We had been out of it for many hours, even as our bodies sometimes pitched and spasmed. The staff had just reviewed George’s condition – it was particularly grave. We had been losing ground ever since being been brought in, and now there was no ground left to yield. George’s uncle was there in the hall. After conferring with the others, Dr. Morris came over and said, It’s time to call the priest – they won’t live much longer. Morris explained the lack of oxygen would shortly cause a full system collapse. There was probably not more than an hour or two left. George was nearly gone already.

As I observed this exchange, at first it didn’t bother me in the least. I registered no emotion, no feeling about the impending exit of me and my best friend from this bed, this building, this Earth. But then something happened – it dawned on me that this was not a dream. It might appear as one, even feel as one, but this wasn’t a theater scene like in Christmas Carol. It was actually happening. It was real – this really was the end.

Suddenly, this whole thing was not right, not right at all. I knew what was happening and I was not willing. I began to struggle and rebel. Even in the truly lost state I was in – with my body killing itself, my mind blacked out, with no oxygen and no hope – I was not ready for what I knew was coming. I would not yield. I knew I had to get back into my body and fight. Fight! Fight like hell! I’m not going! It’s not my time!

Sometimes there’s no better way to say it: It happened in the nick of time. That nick is real and it saved my life. While we’re discussing it – and for your edification in case you don’t know – “nick” was a term in use way back in the 16th century. Its meaning was “the critical moment” – an inflection point, if you will, that could bend the arc of fate one way or another. As such, it is very appropriately conjured here in the description of these events. There’s never been a better time for a “nick” in my life.

The Lasix made us pee. And pee. And pee. We urinated continuously for weeks. No sooner was an empty pee bottle brought, than a new one was needed. Before Cocci, prior to entering the hospital, I weighed 192 pounds. When I finally turned the corner, I weighed 130. I pissed away 30% of my body weight in just a few weeks. There were similar numbers for George.

Our liver and kidney functions continued to fall away, while our bodies constricted blood flow to maintain the heart and brain. But just as the door on our lives was closing shut – there occurred an infinitesimally small skip in time – a blip in the unforgiving march of the machines. It was a tiny, imperceptible little pause – just a slight one – but it happened in the nick of time, as the saying goes.

A few moments later, there was another. And then, another. After a short time, they connected together, showing as a readout on the monitors: the vital signs slowed their decline. Interestingly, it happened for both of us at about the same time. Eventually, the screen figures leveled off. After some longer time, there appeared a tentative uptick in the oxygen saturation. The gamble was paying off.

It worked: The Hail Mary pass the doctors devised, quite literally, saved us just before we expired. The forced dehydration slowed, and then reversed, the fatal buildup of fluids. Our death sentence was stayed at the 12th hour. The Grim Reaper hung around for a couple days but gradually things turned solidly around and the Specter of Death faded away.

Life began to flow back. It was very, very, slow. They continually tapped our lungs, draining fluid, and we continued to pee. They pumped in drugs to help our vital organs. They gave us saline, chemicals, and medications. It took weeks to crawl out of that deep, dark hole. But with the help of our medical team, we were alive.

When things stabilized, we got transferred back to regular ICU. That’s when the team went after the fungus itself, the underlying source of all the problems. They attacked it with a particularly lethal chemotherapy drug called Amphotericin B, known in the trade as “Ampho-terrible”. It’s so toxic that your body rejects even the smallest dose. Your brain must be tricked into allowing the injection.

The preferred method is to blitz your mind out with Demerol – a powerful opioid. Once our brain was in orbit around Pluto, they’d give us the Amphotericin B, sneaking it in while our brains were on holiday. Every two days we had to endure the injection, scrambling our minds as well as our body chemistry. The cure was nearly as bad as the disease: It caused terrible nausea and vomiting along with spasmodic episodes – known as “the rigors” – which were as unpredictable and as powerful as Gran Mal seizures. Wickedly, it took 48 hours to start feeling normal again – just in time for the next dose.

The red rash, in the meantime, had spread over us completely, enveloping our body and killing off the outer layers of skin. It even attacked the insides of our mouth. In the course of our recovery some weeks later, George and I played little contests with the necrotic tissue, peeling off pieces of dead skin like so much old paint from a dilapidated building. There were two categories to our macabre game: Largest single piece, and most pieces in one sitting. This went on for several days. I don’t recall who won what when, but the nurses were thoroughly unamused.

Finally, there came the glorious day we got transferred to a regular unit, outside of the ICU. It felt triumphant. The room had a window! The miracle of sunshine spilled across our beds and we felt like Phoenixes rising. I remember so well the first day in that room – Hallelujah! I sat in bed and thoroughly enjoyed the sunlight falling on my arms. I just kept staring at them, turning my hands over and over in the sun, thinking to myself, We should never take sunshine for granted! Never! I’m sure people thought I was stoned. I probably was.

It was weeks before we were able to get out of bed and start down the long road of rebuilding our bodies but we made steady progress. We had to teach our legs how to walk again. When we were finally able to get to the bathroom on our own, it felt like winning an Olympic event. Soon after, we were walking up and down the halls. And then stairs. Me and George were a team – we always went together. The doctors dubbed us the Cocci Twins. To this day we own that title.

After nearly two months, we’d stabilized to the point where the future was no longer an abstract hope. We still had many months of chemo ahead, but we began to dream of a normal life again. In September George was flown home to DC to continue treatments at NIH. I stayed on at LDS for another couple weeks and was then transferred to Minnesota’s Mayo Clinic in October.

I was at Mayo for weeks. Because I was no longer in danger of dying, I was ensconced in a cheap motel down the road from the clinic. It was supposed to be more “cheerful” than living in the hospital. But the place was a rat hole, so it’s debatable if there was any positive influence about it. After the initial onslaught of tests, my free time began to increase and during my chemo off days I did my best to find some normalcy in life.

By the time we got out of the hospital, we were skin and bones – looking for all the world like survivors from Auschwitz. We had so little body fat and flesh that we literally could not sit on a regular chair or bench because it hurt too much. For over a year we carried our own pillows to sit on! Since we’d lost so much body weight, gaining it back became a top priority. Eat anything you want! Eat everything! And a lot of it! was the advice of my Mayo physician, Doctor VanScoy.

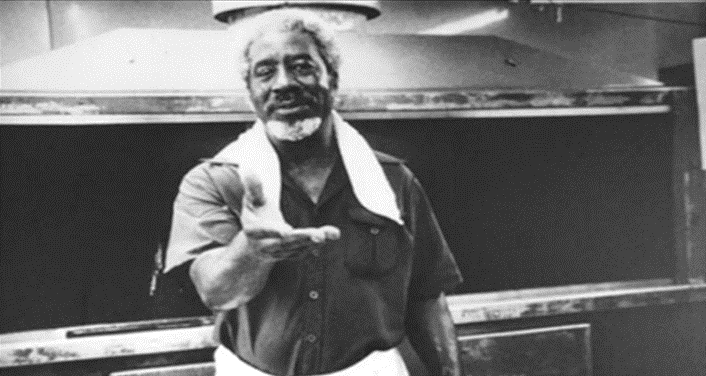

Having spent a lot of time in the southeast, I had a taste for good old Southern Bar-B-Que. But this was Minnesota – Land of Lutefisk! – and the chance of finding anything genuine was slim. So I was surprised to hear of a place called Hardy’s BBQ not far away that had a good reputation. I was doubly surprised to discover it was truly authentic. After my first life-saving BBQ at Hardy’s I was determined to meet the owner and see the person behind this accidental enterprise.

I finally met the man himself one day. John Hardy maintained a small picnic table out back where he and the staff would take breaks. John was an instantly likeable older Black man with white hair and a short white beard. Each day I could manage it, I’d take a bus to Hardy’s and would chat with him at the picnic table. He took a keen interest in my difficulties and was very kind and encouraging. No matter what – you just have to keep a-goin!, he’d say.

After a few weeks I transferred from Mayo Clinic to Hennepin Medical Center in the Twin Cities where I became an outpatient while I lived with my parents in Bloomington. The chemo kept on for almost a year – every other day. The object was to keep the dose of “Amphoterrible” in your bloodstream high enough to eventually kill off every last vestige of the Cocci. During those endless dark days of winter, George and I talked on the phone regularly, cheering each other on. Tough it out, brother…we’re making progress.

The next summer I recuperated on the North Shore of Lake Superior, an inspiring place to revitalize your soul if there ever was one. But, Amphotericin flashbacks impaired me for years. They would come on with abrupt intensity – I’d suddenly black out and flash into rigors on the spot. Thankfully, there was a warning. Strange as it might be, a few moments before the event I would get an intense metallic garlic taste in my mouth. When that happened, I knew what was coming and would immediately lay down on the ground so as to not collapse uncontrolled.

This became an inconvenient, though sometimes humorous, hallmark of my existence during those recuperative times. At flashback times, I would instantly drop down onto the ground. It could happen anywhere, anytime: Walking with friends on a sidewalk, in a restaurant, at the bus stop. There was no telling when it might happen. Those who knew me and my condition would simply say, Here goes Kramer’s Cocci thing again… Those that didn’t, looked on in horror. But, after a couple minutes it was over. I’d get back up and carry on. It was my own quirky performance art.

The following year I moved to Duluth to finish up the few credits left for my degree. There were several Amphoterrible flashback episodes while at UMD, many of them funny. It happened several times during class. But I warned the teacher and those around me in advance. In Algebra II the teacher got quite used to it. He barely paused as my body shook on the floor, Don’t mind Kramer, he’ll be alright… and would move along to the next proof.

Over time the flashbacks gradually faded away. It took about four years before I regained my health and could safely surmise that I was done with the flashbacks. But I’ve never gotten back to the weight I had before Cocci. Ever since, I’ve been holding steady at between 170 – 180 pounds. I still wear the same clothing sizes I did in college. Probably it has something to do with my obsessive determination to stay fit, an ethos I developed post Cocci.

George was at NIH for months. Eventually, he too became an outpatient – for over a year. After leaving LDS he underwent a different chemotherapy regimen with a new drug – Ketoconazole. It seems his results were much the same as mine, although it took him a little longer to recover. He moved to Florida, got married, and has been living the dream in the Sunshine state. The two of us are still best friends and have had many great adventures together since the end of our former lives.

And the fossils? George has the bear skull, I have the sabre-toothed tiger bones. We donated all the rest – many dozens of bones – to the Science Museum of Minnesota, a place very far away from the San Joaquin Valley and its namesake disease. I had befriended Bruce Erickson, the head paleontologist there, a few years after Cocci when I moved to the Twin Cities for a job. He was thrilled to get a collection of Pleistocene bones from the iconic California tar pits.

So, this brings us full circle to the premise I related at the beginning of all this: What you don’t know might actually kill you. Yet, it must also be noted, sometimes it doesn’t. Sometimes in life you find that the Hail Mary gamble – the one with the longest of all odds against it – is the one to take. If it pays off, you just might find yourself alive in the morning.

AFTER WORDS

Each year, many thousands of people are infected with Valley Fever, mostly in the Southwest, and by all accounts the numbers are increasing. This is probably due to a combination of factors – global warming has increased the deserts, while population growth has increased the development in such places.

As you’ve heard several times by now, over 90% of Cocci cases are no big deal. Many people don’t even realize they have the disease. Of the other 10%, most have Flu-like symptoms of varying intensity.

Because we had inhaled an immense intake of spores, George and I reached the very top of the unluckiest 1% of the worst cases on record. Ours was the extreme of the extreme. Ultimately, we ended up being the two most severe victims of pulmonary Coccidioidomycosis ever to have survived. That still holds true today, nearly four decades hence. Don’t try and break our record! The saga of our ordeal has been written up in medical journals like the American Review of Respiratory Diseases. The papers have many references, nearly all of which, tellingly, are post-mortem reports.

Now I’m going to get all spiritual on you:

Since that fateful time in the early 80s, I have lived an incredibly full, vibrant, and rich existence – sometimes by accident, but mostly on purpose. From the time I knew I would survive, I made a conscious decision to make the most of my life: mentally, physically, emotionally, and spiritually. Ever since Cocci, my life has been one that overflows all those aspects. The first two – mental and physical – have been relatively easy. The third – emotional – a little more difficult.

And the fourth? Let’s just say spirituality was not much a part of my world before Cocci, (the time which George and I refer to as“BC” – Before Cocci). I didn’t understand the concept of God, or Allah, or whatever you want to call it. For me it didn’t much exist. Nor, not exist. I simply didn’t think about it. You could say I was agnostic. That’s what I told people before I got Cocci.

But since it happened, I’ve spent many hours pondering our miraculous life-and-death event and its meaning to me. In retrospect, I am thankful to have gone through Cocci. Perhaps it was even, in a way, necessary for me to go through it. It’s helped me to understand there is much more to life than what we see, hear, touch, feel, taste, and measure. I’m no evangelist and I’m certainly not religious. The closest doctrine for me is Buddhism, but even that falls short of the oceans where my soul surfs these days.

I was fortunate to get a glimpse of what is beyond this life and yet still come back and live more of it. The journey has had a profound impact on me spiritually and is manifested in my approach to life and living. Before my experience I never much thought about the God thing. I never seriously paid any attention to the idea. But after Cocci I did. And I do still. Whatever way you may wish to define “God”, it’s my conviction that it/her/him is real. Real in the sense that it exists, although – being mere humans – we cannot fathom that existence. There are plenty of affirmations of this if only you open your mind to them.

Perhaps you are skeptical. I don’t blame you. I certainly was, all through my BC years. I dare say I would still be agnostic if not for Cocci. Going through that experience and processing the evidence of it, I had no choice but to realize that something profound was working in the background.

Ours was a very strange and complex case. For your review, I offer the following simple twists of fate that happened in a few short days and guaranteed our survival. Individually, they are each unlikely occurrences that may, or may not, be viewed as coincidental. Yet the omission of any one of them would have resulted in our demise. But when you stack them all together – which is exactly what happened to us – what are the odds of such a collective “coincidence”? I leave you to make your own conclusions. I’ve made mine:

- a) At the time of our crisis, there were only three places in the entire continent that had respiratory ICUs capable of coping with our condition: NIH in Washington DC, UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles, and LDS Hospital in Salt Lake City. We were on a long, circuitous road trip and had stopped in Salt Lake City on a whim.

- b) Our digging in the tar pits had no timeframe – we could have stayed a month, or left days before we did. It was dictated by when the bonebed played out. As it turns out, the bonebed dried up and we left the site at the exact right time to end up in Salt Lake City just before our symptoms kicked in.

- c) We were on our way to the Tetons and just happened to stop in Salt Lake City for one night. If we had been a day or two earlier, we would not have come down with symptoms in Salt Lake and would have carried on to Wyoming, setting up camp at 10,000 feet. In that case, we would have come down with Cocci once in the mountains and would have certainly died in our tent.

- d) The morning we decided to definitely leave Salt Lake – despite being ill – the timing chain on the van blew out, forcing us to stay put. It wasn’t a fan belt, a broken water hose, a faulty carburetor, a wacky alternator, or any number of other more common problems– all of which we could fix ourselves – it was something far more serious, something we positively couldn’t handle, and it forced us to stay put. That was the day Cocci really hit us. The next day we were in ICU.

- e) After the wasted time at Cottonwood Hospital, our admission to LDS was just in time to save our lives. If Cottonwood had admitted us for observation – as was their initial inclination – we would likely have died there that very night because they were ill equipped to deal with our condition.

- f) Even so, the LDS the doctors, at first, tried to send us home. If we had complied, George’s uncle Howard would have had to deal with two dead bodies the next morning. As it happened they admitted us in barely enough time to address our situation as it became critical.

- g) Two of the three beds in the LDS Respiratory ICU happened to be open when we got there. The unit was full up until that very morning.

- h) Our team of doctors came up with a daring plan at the 12th hour – a Hail Mary pass that had never been tried before. It worked, just barely, in the nick of time.

I was about to wrap up this story and start my conclusion by saying In the end… Yet it occurs to me that George and I have, thankfully, not reached the end of our story. To be sure, we did have an end – a strange and terrible end in 1983. That volume of our lives BC – before Cocci – has been closed these many years. But since that time, there’s been a new book, and a whole new series of adventures – separately and together – for the Cocci Twins.

Viva la Vida!